by The Very Rev. Michael W. DeLashmut, Ph.D.

I don’t think anyone who lives or works at GTS and worships regularly in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd can walk away unchanged. The rhythm of daily prayer in that sacred space formed me as a Christian and a priest, and serving as the Dean of the Chapel has afforded me the privilege of stewarding its legacy—ensuring future generations of students carry forward the uniquely transformative spirit of GTS into their ministries.

I often describe the Chapel as a sermon written in stone—indeed, multiple sermons, expressed in stone, wood, and glass. Each of these sermons points toward the transformative love of God in Jesus Christ, continually sending us forth into service, echoing the carving on the chapel steps: “Blessed are they who enter the gates into the city.”

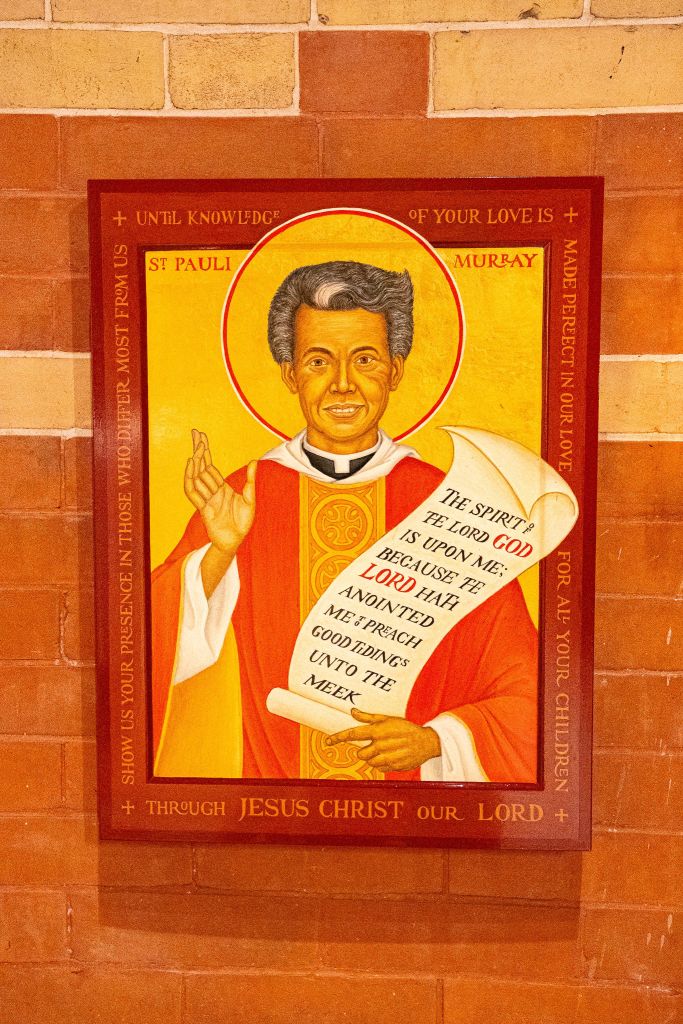

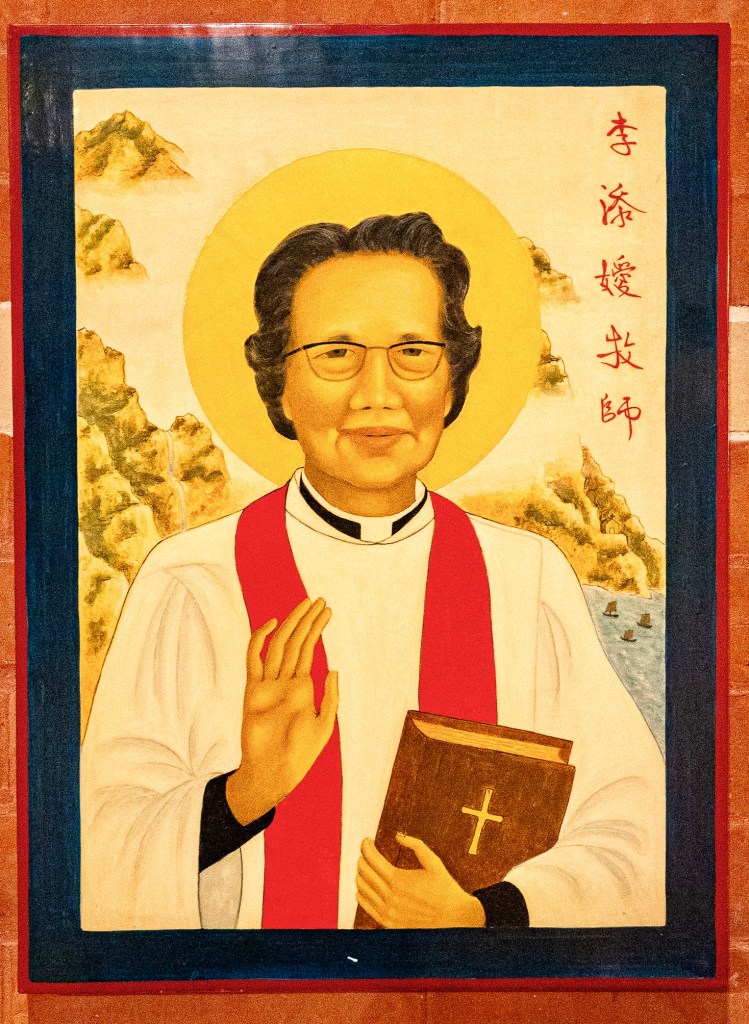

A particularly meaningful aspect of our chapel for me are the three icons flanking the chancel steps: Alexander Crummell (commissioned by the Class of 2001), Florence Li Tim-Oi (commissioned by the Class of 2005), and the most recent, Pauli Murray, which I commissioned in 2021. Our approach to these icons at GTS, while informed by Orthodox devotion, also incorporates an Anglican dimension. In a recent article for the Anglican Theological Review, I explored how these icons in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd foster something akin to “social holiness”—an approach to spiritual transformation that is deeply intertwined with justice, reconciliation, and active service to the world.

Icons in Worship

The use of icons in worship has experienced a tumultuous history in the Church, marked by periods of controversy and revival. From the Iconoclastic Controversy of the 8th century to the iconoclastic impulses among Puritan Anglicans in the 17th century, visual representations in Christian worship have frequently been points of theological contention. Within our tradition, the relatively recent revival and appreciation for icons corresponds closely with the modern Anglican-Orthodox dialogues that emerged prominently in the 20th century.

These dialogues have significantly enriched Anglican theology, deepening our understanding of patristic sources, incarnational theology, and sacramental practices, and opening new pathways for spiritual and theological exploration. Two notable milestones from these dialogues include the Moscow Agreed Statement (1976) and the Dublin Agreed Statement (1984). Both statements underscored theological commonalities between the two traditions, particularly around the theology and practice of iconography. The Moscow Statement affirmed Anglican recognition of icons as valid expressions of incarnational theology, while carefully distinguishing between veneration of icons and worship due exclusively to God. Similarly, the Dublin Statement expanded on these affirmations, articulating the Christological foundations of icons as visible embodiments of the Incarnation—icons as “visible gospels,” allowing worshippers to “confess and appropriate the mystery of the Incarnation.”

One of my first experiences of worship with icons was at St. Mark’s Cathedral in Seattle, attending Compline as a young adult. Though I had read about icons, encountering an Orthodox icon of Christ Pantocrator in that sacred space was deeply moving. Immediately, I sensed something like a window into God’s all-encompassing love and presence. This profound personal experience illuminated for me how icons might function within worship spaces—not merely as aesthetic artifacts but as tangible, contemplative encounters with divine love.

Today, many Episcopal churches incorporate classical forms of iconography consistently with Orthodox ascetical theology and notions of theosis. Yet equally significant is the presence of icons depicting contemporary saints, approached not only as windows into the divine mystery but also as inspiring embodiments of justice-oriented spirituality and social holiness. This dual purpose of icons—contemplative devotion and active inspiration toward justice—provides the interpretive lens through which I understand the icons at the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, pointing us both inward toward spiritual transformation and action.

Rowan Williams on Icons

All of my students know that Rowan Williams’ work has made a profound impact on me. From my early days as a graduate student discovering Williams’ writing, to the great privilege of teaching alongside him at GTS last year, his integration of Orthodox and Anglican theology and spirituality have shaped my own theological understanding and, indeed, his short devotional books Ponder These Things and The Dwelling of the Light, have similarly informed my appreciation for icons as a means of spiritual and moral transformation.

In Ponder These Things, Williams invites readers into contemplation through icons of the Virgin Mary, emphasizing Mary’s role as a pathway to deeper engagement with the mysteries of Christ’s incarnation and redemption. Williams’ emphasizes that icons are more than artistic representations, but windows inviting us into direct, contemplative encounters with the divine. Similarly, The Dwelling of the Light extends this contemplative practice through icons of Christ, including powerful images such as the Transfiguration, the Resurrection, Christ Pantocrator, and Rublev’s renowned Hospitality of Abraham. Williams characterizes icons as “performative”—their creation and veneration functioning as spiritual actions, rituals designed to facilitate transformative encounters with God.

Through Williams, and indeed through the rich theological environment fostered by past and present colleagues at GTS, I have gained a deep appreciation for the Eastern theological perspectives and Williams’ theological synthesis resonates with me—particularly his emphasis on Eastern Trinitarian theology, the distinction made between the essence and energies of God, and the unique Orthodox perspectives on original sin, salvation, and deification.

Of course, Rowan Williams stands within a broader Anglican tradition of engaging Eastern theological thought. Historical figures such as Lancelot Andrewes similarly displayed an affinity for Eastern spirituality and theological motifs, demonstrating that Williams’ engagement is part of a longstanding Anglican openness to Orthodox theological richness, even though our more overt engagement with the Orthodoxy is more a product of the 20th century. Williams, however, brings these themes into contemporary practice, clearly articulating a devotional theology of icons that integrates Orthodox contemplative traditions with Anglican spirituality.

Ultimately, Rowan Williams’ reflections underscore the potential of icons to act as powerful spiritual resources within Anglicanism—not just aesthetic objects but dynamic means of grace, inviting believers into the presence of God and forming them into agents of spiritual transformation and justice.

Icons in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd

The three icons prominently displayed in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd—Alexander Crummell, Florence Li Tim-Oi, and Pauli Murray—each tell a complex story of resilience and faithful witness amid institutional marginalization and repression. These icons serve as poignant reminders of our complicated relationship with these remarkable figures and the Church’s historical failures to fully embody the radical inclusivity, justice, and diversity called for by the Gospel.

Alexander Crummell (commissioned by the Class of 2001) was the first African American priest ordained in The Episcopal Church. He is known as an educator, innovator, and missionary, but his admission to GTS was denied out of fear of alienating the seminary’s majority-white donors and board members. Despite this rejection, Crummell’s life was defined by perseverance and a profound commitment to racial justice, theological education, and spiritual leadership. The icon, painted by The Rev. John Walsted—an Episcopal priest and iconographer within the Diocese of New York—depicts Crummell in traditional priestly vestments, holding a scroll inscribed with words from one of his sermons: “We must receive as freely as we give, for only thus do we truly embody the power of Christ’s reconciling love.” The icon’s gold-leaf background symbolizes divine presence and holiness, framing Crummell as a figure of spiritual maturity and enduring wisdom.

Florence Li Tim-Oi (commissioned by the Class of 2005) was the first woman ordained as a priest in the Anglican Communion. Her ordination during World War II was later pressured into suspension by Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple due to fear of controversy within the Anglican establishment. Li Tim-Oi’s steadfast faith endured through severe persecution during China’s Cultural Revolution. Her icon, created by Sr. Ellen Francis OSH, a student of Walsted, uniquely incorporates Asian artistic influences into the Orthodox style, portraying Li Tim-Oi in traditional clerical attire with a Book of Common Prayer in hand. The serene landscape behind her symbolizes her enduring spiritual resilience and cultural identity. This icon stands as a powerful testament to The Episcopal Church’s commitment to gender equality and recognition of the full inclusion of women in ordained ministry.

Pauli Murray’s icon, which I had the honor of commissioning in 2021, completes this triad. Murray, a pioneering African American lawyer, activist, theologian, and priest, faced profound challenges at GTS, including racism, misogyny, and homophobia—factors which ultimately contributed to their decision to transfer to Virginia Theological Seminary. The icon, written by Zachary Roesemann (another Walsted student), depicts Murray in a vibrant vermilion chasuble, highlighting their groundbreaking ordination and passionate advocacy for justice. Murray holds a scroll inscribed with Isaiah 61:1, a prophetic scripture Murray cited while advocating for women’s inclusion at GTS in the 1970s. Notably, Murray’s halo and scroll extend beyond traditional iconographic borders, symbolizing a ministry transcending institutional limitations and barriers.

These three icons share a common artistic lineage through their association with iconographer John Walsted and their provenance within the Diocese of New York. While deeply influenced by traditional Orthodox forms, each icon thoughtfully expands and creatively engages these traditions rather than merely replicating them. Together, they embody a vision of Anglican social holiness—icons serving as both windows into divine mystery and vivid reminders of the ongoing call to embody justice, reconciliation, and radical inclusion within our communities.

The Use of icons in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd

Candles are lit beside the icons of Alexander Crummell, Florence Li Tim-Oi, and Pauli Murray whenever students gather on the Close, drawing our community’s attention to these holy figures. Although we have made local adjustments to our liturgical calendar—observing Florence’s commemoration (January), Pauli’s commemoration (July), and Alexander’s commemoration (September) during intensive sessions in May, August, and January—we strive faithfully to honor their feast days within our communal worship.

These icons hold particular significance during a newer penitential tradition at GTS. At the beginning of each academic year, just before our first Solemn Evensong and Matriculation ceremony, our community participates in an acknowledgment of intersectionality, recognizing our institutional complicity in historical injustices, exclusion, and marginalization. Standing in the chancel, flanked by these three icons, we confront our past failures and collectively seek God’s mercy and strength to build a more inclusive and just future. In this moment, Crummell, Li Tim-Oi, and Murray symbolically stand alongside us—three faithful servants of Christ to whom the church has historically said “no”—precisely at the place in our worship where God definitively says “yes” to us in the Eucharist.

When giving tours of the chapel, I often reflect on this powerful juxtaposition. These icons serve as vivid reminders of the prophetic tradition articulated in the temple sermons of Amos (5:18–27), Micah (3:9–12), and Jeremiah (7:1–15), each emphasizing that worship without justice is an offense to God. Indeed, these icons of reconciliation call our community continually toward the realization that authentic worship always leads to active participation in God’s transformative work of justice in the world.

Conclusion

Ask any current hybrid MDiv student what GTS means to them, and they will undoubtedly speak about the Chapel of the Good Shepherd and the lasting impact this sacred space makes on their lives. As I look forward to the Chapel’s future, particularly in the context of our expanding hybrid MDiv program and the future presence of Vanderbilt students on the Close, I feel both excitement and profound responsibility.

In my role as Dean of the Chapel, I am committed to continually sharing the story of this remarkable place: of a seminary established by the General Convention of the Episcopal Church, planted in an apple orchard of a faithful scholar and lay person; a chapel built intentionally as a “sermon” in stone, wood, and glass, dedicated to forming Christian leaders in the image of Christ the Good Shepherd; of a community where virtues are cultivated through disciplined prayer and infused by grace through the sacraments; and a community formed by saints like Alexander Crummell, Florence Li Tim-Oi, and Pauli Murray, who inspire and accompany us as we “leave the gates and enter the city.”

This enduring story is one of both continuity and renewal—honoring our rich traditions while embracing new possibilities. As future generations from Vanderbilt and GTS come together in this cherished space, I look forward to witnessing how the Chapel of the Good Shepherd continues to shape faithful leaders committed to transformative justice, radical inclusion, and vibrant witness to the Gospel in our world.

Leave a comment